“Love me tender, love me sweet, never let me go. You have made my life complete and I love you so.”

Oh, how the world has changed since 1956. The year that Elvis Presley released the chart topping, ‘Love me tender’. The 1950’s saw the concept of love and relationships romanticised and intimacy consisted of courtship and hand holding. Today, we have become acclimatised to ‘screened intimacy’, with the proliferation of the internet and social media, making way for the rise in popularity of online dating as a preferred method of meeting ‘the one’.

The growth of the internet and various social media applications has transformed the way, in which, we initiate and maintain personal relationships. Messages, photographs, videos and texts can all be exchanged through cyberspace, in an effort to impress the recipient in the hopes of scoring a date. The process of finding and encountering romance is fundamentally different to the ‘love me tender’ days, as new forms of media allow for individualised needs to be met, in terms of a preferred way to meet and pursue new people.

With 20,000 new downloads each day (Wortham, 2013), Tinder has, arguably, become the most popular dating application with over 10 million daily users, looking for that special someone. The name itself, together with the bonfire icon that accompanies the brand name, insinuates that once users have found a match, sparks will inevitably fly and ignite the fires of passion.

This insinuation, however, was not the result of my most recent Tinder encounter. Upon matching on Tinder, myself and ‘he who shall not be named’, began conversing via the applications messaging system. We then continued this conversation on various other social media outlets, inclusive of Facebook, Snapchat and Instagram. After chatting online, on and off for a couple of months, we finally decided it was time to bite the bullet and meet up, face to face (dun dun dun).

Upon arrival to our date location and meeting each other for the first time, it was clear that there was, however assured by the name and icon of the Tinder application, no spark between the two of us. After the initial date, we both agreed not to see each other again, although we have remained friends till this day (online that is).

This experience, to Elvis Presley, would surely, have seemed otherworldly, meeting someone initially online, with chemistry flying across text messages, to having absolutely no chemistry at all in the real, physical world. This auto ethnographic recount of a failed tinder date has informed my thinking about how we understand the concept of screened intimacies and why people feel more comfortable conversing online as opposed to in person. It has also prompted me to ponder on why it is it may seem as though there is chemistry between two people in an online setting, but when tasked with meeting and maintaining conversation in the real world, this is evidently not the case.

To my failed tinder date, I thank you for being my muse for this blogpost, for without you I would have never known awkward silence like I did that day.

References

Sumter, S 2017, ‘Love me Tinder: Untangling emerging adults’ motivations for using the dating application Tinder’ Telematics and Informatics, Vol. 34, No. 1, pp. 3-7

James, J 2015,’ MOBILE DATING IN THE DIGITAL AGE: COMPUTER-MEDIATED COMMUNICATION AND RELATIONSHIP BUILDING ON TINDER’ Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 1-21

David, G 2016, ‘Screened Intimacies: Tinder and the Swipe Logic’ Social Media and Society, Vol. 1, No.11, pp. 1-5

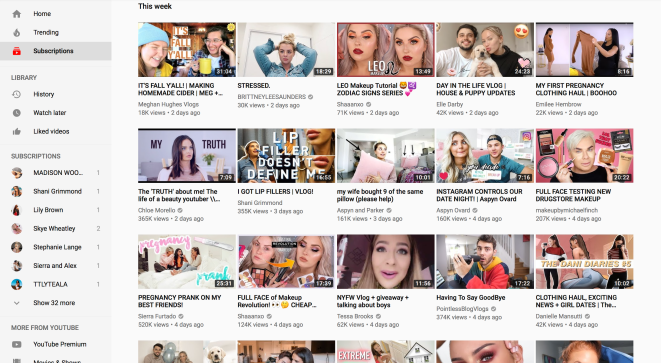

Despite my initial concurrence with the idea that program streaming is a new concept that has allowed for improved access to television, the more I pondered, the more I realised, watching television at a time after the program has aired and being able to watch a particular program, movie or episode over again, is not such a new advancement. This realisation brings me to share my earliest television memory.

Despite my initial concurrence with the idea that program streaming is a new concept that has allowed for improved access to television, the more I pondered, the more I realised, watching television at a time after the program has aired and being able to watch a particular program, movie or episode over again, is not such a new advancement. This realisation brings me to share my earliest television memory.